As of the date this blog post was written, Governor Polis’ statewide stay-at-home order remains in effect until April 26th. Many school districts in the Denver Metro area recently announced their decision to utilize remote learning for the rest of the school year. It seems clear that it will be awhile before we’re back to “business as usual.”

Our buildings may be closed, but libraries are still finding creative ways to serve their communities! Libraries are chatting with users from afar, signing up folks for digital access cards, streaming online storytimes, hosting virtual book clubs and more. As we explore online programming and connecting with our communities in new ways, I encourage us to think about how we can make these experiences accessible and enjoyable for all.

Video and Web Accessibility Rights

As public institutions, libraries have a legal obligation to make our services and programs accessible. Although the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) did not specifically address equal opportunity in regards to the internet when it was passed in 1990, several court cases since then have demonstrated that video and web accessibility is a right. Some of these landmark cases include:

- 2006: National Federation of the Blind v. Target Corporation

- 2011: National Federation of the Blind v. Penn State University

- 2012: National Association of the Deaf v. Netflix

- 2013: Greater Los Angeles Agency on Deafness (GLAD) v. Time Warner, Inc.

In each case, the courts ruled in favor of the plaintiffs or the organization settled and made their services fully accessible.

Most libraries are required to provide equitable access and services for individuals with disabilities under either Title II (Government Programs and Services) or Title III (Public Accommodations) of the ADA. If libraries receive any federal funding, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 also applies. For more information about local and federal accessibility laws, please refer to:

- 3Play Media: Accessibility Laws

- 3Play Media: Colorado State Accessibility Laws

- 3Play Media: Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Video Accessibility Requirements for Web

Rather than provide captioning and other auxiliary aids because we must, I hope to see libraries embrace accessibility because we should. We can’t say libraries are for everyone without also looking for ways to make our spaces, services and programs accessible for all – whether in the library or online.

Disabilities in Your Community: A Personal Perspective

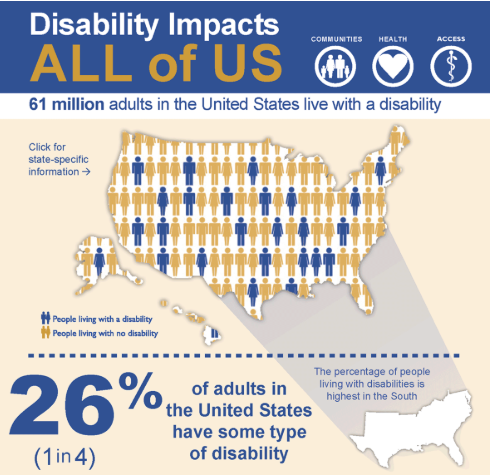

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 4 adults in the United States and 1 in 6 children experiences disability. These disabilities may include physical disabilities, such as deafness or vision loss. They can also include mental illness, chronic illness, or “any condition of the body or mind that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities and interact with the world around them.” Disabilities may be legally acknowledged or otherwise, temporary or permanent, constant or episodic, visible or invisible.

Whether we are aware of it or not, we have coworkers and family and friends and library users with disabilities. If we’re not aware of this need in our communities, I would suggest this indicates both barriers to access and a lack of trust in our libraries. There is no community without disabilities. As S Bryce Kozla says in an ALSC Blog guest post about disability in the children’s area, “the reason that you might not see people with disabilities in your library is because your space is inaccessible or otherwise unwelcoming to the disability community, and word has gotten out.”

The same applies to our online library. If individuals with disabilities are not engaging with our online content, it’s not because they don’t want to – it’s because we’ve made our content inaccessible. Perhaps our videos are inaudible and uncaptioned. Perhaps we are equipping staff with microphones and providing captioning, but families who need this service don’t know about it because we’re not advertising it.

Speaking from my personal perspective as an individual with disabilities, I’m much more likely to disengage with an organization rather than identify myself and make a request… especially if I have to request obvious accommodations that enhance everyone’s user experience (like captioning). By treating accessibility as something available only by special request, libraries run the risk of appearing unwelcoming and uncaring.

Accessibility is Essential for Some, Better for Everyone

When it comes to virtual programming, four categories of disabilities greatly impact an individual’s viewing experience. These include:

- Visual: such as blindness, color blindness, low vision, photosensitivity, tracking difficulties

- Hearing: such as deafness and hearing loss

- Motor: such as limited or severely impaired fine motor control, arthritis, cerebral palsy

- Cognitive: such as learning disabilities and attention difficulties

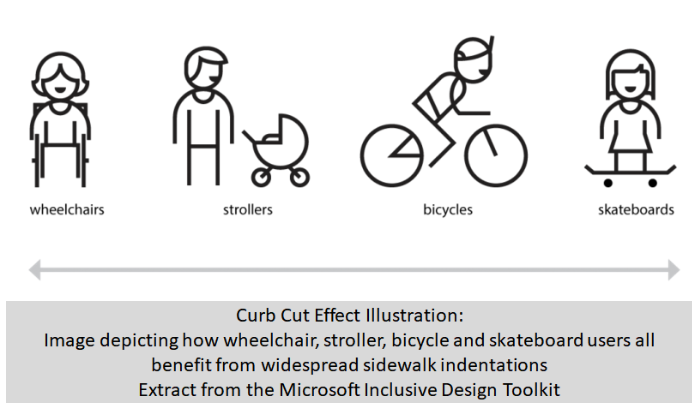

Accommodations are essential for certain groups to access our content, but they also improve everyone’s experience. Consider the ramp requirements introduced by the ADA. Everyone benefits, not just the intended audience of wheelchair users: stroller rollers, travelers with luggage, my mother-in-law’s bad knees. Think about how great automatic door openers are for helping prevent the spread of germs! This is called the Curb-Cut Effect:

The same can be said when designing online experiences. Alternate text helps both individuals with vision loss AND individuals whose internet won’t load images. Everyone is more likely to read information that is presented in large text and good color contrast. Platforms that require minimal clicking to navigate benefits both those with limited fine motor control AND caregivers who are holding babies on their laps while watching your storytime. Captions assist both those with hearing loss AND those with busy, noisy backgrounds. Considering the entire state is under a stay-at-home order, I can almost guarantee your storytime viewers will be battling increased background noise! Check out this article from UW-Madison’s Dr. Morton Ann Gernsbacher about how Video Captions Benefit Everyone.

Building in Accessibility from the Start

Accessibility is much easier to build in from the start! Rather than wait for library users to make requests and apply patches to inequitable systems, let’s look at how we can apply inclusive design principles to create accessible and enjoyable online experiences for all.

The term universal design was coined by architect and wheelchair-user Ronald Mace. The Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University defines universal design as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without adaptation or specialized design.” The seven principles of universal design are:

- Equitable Use

- Flexibility in Use

- Simple and Intuitive Use

- Perceptible Information

- Tolerance for Error

- Low Physical Effort

- Size and Space for Approach and Use

POUR is another helpful framework for thinking about our multimedia web content. POUR is an acronym for the four guiding principles behind the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). The four design principles are:

- Perceivable: Anyone can discern the information and content, regardless of how they perceive it

- Operable: The interface is navigable and responsive to users

- Understandable: The interface operation and information is clear and easily discoverable

- Robust: The content is flexible and compatible with adaptive technologies

When considering which social media and video sharing platforms to use for virtual programming, leadership might ask…

- How intuitive is this platform?

- How many clicks does it take to engage with our content?

- Can this platform be accessed with adaptive computer technologies?

- If a user accidentally exits the virtual storytime or program, how easy is it to access again?

- How will we provide captioning?*

*Although most children in our storytime audiences aren’t reading yet, their caregivers are – and caregivers are an ESSENTIAL component of both high quality storytimes and high quality screen time experiences for young children. By empowering caregiver participation during virtual storytimes, libraries can offer families a constructive, connective and developmentally-appropriate screen time experience.

When planning and delivering virtual storytimes, storytime staff might ask themselves…

- How can I reduce background noise and visual busy-ness in my filming environment?

- How can I position myself so that my mouth is always visible when speaking, reading or singing?

- How can I adapt this song or rhyme so that children and families with a variety of motor abilities can participate?

- How can I adapt this flannel activity so that children and families with colorblindness can participate?

Most importantly, libraries should look at who is involved with our online program planning and revision processes. Individuals with disabilities can share valuable insights and lived experiences that will make your online programs and services better for everyone. Why not invite us to the table?

As our libraries primarily shift to interacting with our users over the web, we have a unique opportunity to connect with community members who may have never seen the library as a place for them. What if accessibility is a right, not a request? How does that change the way we plan and deliver our programs and services? Let’s take this time to learn and do better by our disability community – both now AND in our future “business as usual” operations. When we do, everyone benefits!

Resources

Whether or not your library has jumped into online programming, it’s never too late to take steps towards accessibility! The following resources can help:

Rooted in Rights: Accessibility

If you explore only one resource from this list, start here. Rooted in Rights, a project of Disability Rights Washington, both produces and advocates for accessible creative content. Their Accessibility page includes information about and additional resources for captions, audio descriptions, transcripts, alt text and image descriptions. Be sure to check out the Video Accessibility Guide for great tips on getting started with or outsourcing captioning.

3Play Media: Video Accessibility Checklist

3Play Media provides professional captioning, transcription and audio description services. Their Accessibility Blog is full of free resources and is well worth exploring!

Virtual Storytime Services Guide

The collaborative ALSC and CLEL Virtual Storytime Services Guide includes many resources empowering leadership, virtual program marketers and virtual program providers to design and deliver a more accessible online experience. Includes technology considerations, presentation delivery suggestions, captioning resources and much more!

*Updated 4/14/20: An earlier version of this blog post referred to individuals with impairments. This is not preferred language as it frames people in terms of deficiency; this language has now been removed. I deeply apologize for any harm this caused and appreciate those who came forward and made me aware of this issue.

*Updated 7/29/20: Updated resources list.

Jessica Fredrickson serves on the CLEL Advocacy and Training Committee. She is a former teacher turned Youth Services Librarian. Professionally, Jessica is known for advocating for accessibility and giving storytime flannels early math makeovers. Her favorite things include tea, mountain hikes and middle grade fiction.