Transforming Library Collections Part 2

Approx time: 1hr 40min

This minicourse module is an abridged version of Project READY’s Module 26b: Transforming Library Collections Part 2. Follow the link to access the full module.

AFTER WORKING THROUGH THIS MODULE, YOU WILL BE ABLE TO:

- Discuss some of the key topics that must be considered when collecting diverse texts.

- Develop a plan to stay up-to-date with and address these topics and others that may arise.

INTRODUCTION

There are a number of important topics that need to be considered when collecting diverse texts. In this module, we will highlight several of them for you to think about and act on.

THE DIVERSITY GAP IN CHILDREN’S PUBLISHING

In 1965, Nancy Larrick brought national attention to the need for diverse literature in her landmark article “The All-White World of Children’s Books.” In her study, Larrick found that only 6.7% of the books she examined contained one or more Black characters, and less than 1% featured contemporary African Americans. She concluded that the lack of representation has a profound impact on youth. Larrick identified two consequences of the omission of African Americans from books for children. First, across the country, 6 million children of color were learning to read and to understand the American way of life in books that either omitted them entirely or scarcely mentioned them at all (63). Second, 39 million white children were learning from their books that they were “the kingfish” (63). Larrick concluded:

When the only images children see are white ones…as long as children are brought up on gentle doses of racism through their books… there seems to be little chance of developing the humility so urgently needed for world cooperation. – Nancy Larrick

In 1982, Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop reexamined the “all-white world” of children’s books to determine whether progress had been maintained. In her work, she assessed the status of African Americans specifically. Bishop found that while the number of books had increased, many publishers had fallen into the “trap of knee-jerk political correctness.” She identified three categories of books:

- Social conscious books: books that appeared to be written to help white children understand about the experience of people of color.

- Melting pot books: books that included children of color alongside white children, with no evident differentiation between them. The implicit message: we are all just alike, except for the color of our skin.

- Culturally conscious books: books that were intended primarily for African American children and reflected both the uniqueness and the universality of their experiences.

Bishop was also one of the first to question the authenticity of the writing. She concluded that “at issue is not simply racial background but cultural affinity, sensitivity, and sensibility…The irony is that as long as people in relative power in the world of children’s book—publishers, librarians, educators—insist that the background of the author does not matter, the opportunities for Black writers will remain limited, since they will have to compete with established non-black writers whose perspective on the African American experience may be more consistent with that of the editors and publishers and whose opportunities to develop their talents as writers have been greater.”

Dr. Bishop (1990) is perhaps best known for her argument that youth need books that serve as windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. She writes:

Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange.

These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author.

When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror.

Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.

– Rudine Sims Bishop

Today Larrick and Bishop’s messages still ring true, reminding us that the continued lack of representation in children’s literature remains problematic, must be addressed, and has real-world consequences for BIYOC.

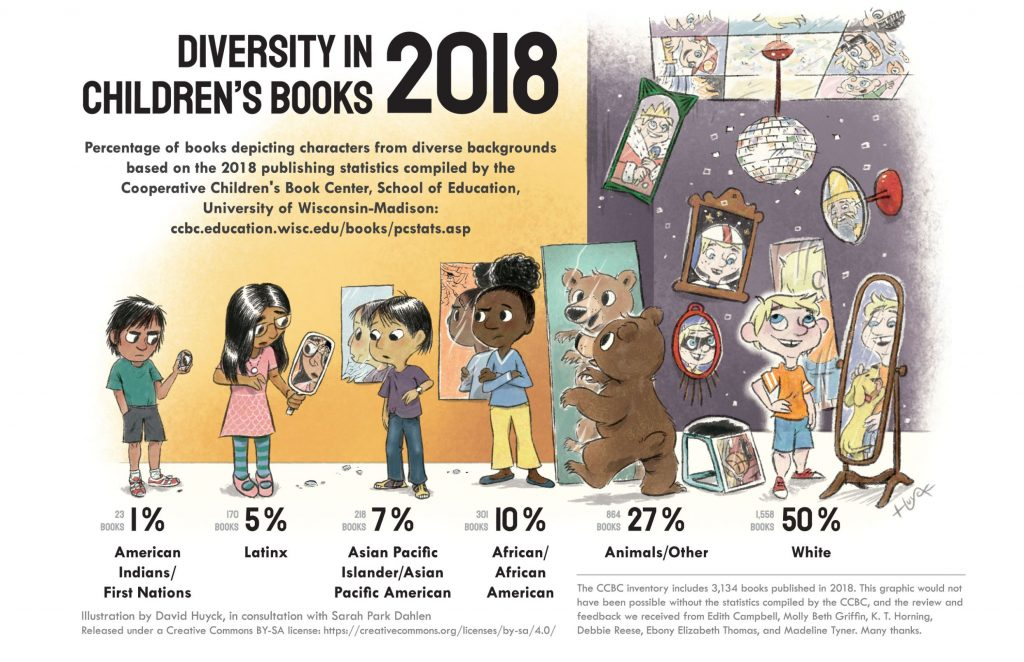

For decades, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) has been collecting statistics1 on the number of children’s books published each year that are by and about people of color and Native peoples. Starting in 2014, the number of diverse books began to grow but it still needs to improve. This infographic, developed by David Huyck and Sarah Park Dahlen in consultation with Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, and Molly Beth Griffin, depicts the 2018 CCBC data. Differences in representation among cultural groups are highlighted by mirrors – larger and more indicating greater representation.

Who is… Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop

Rudine Sims Bishop is Professor Emerita of Education at The Ohio State University, where she has taught courses on children’s literature. To learn more about Dr. Bishop and her work:

- Watch this interview with Dr. Bishop

- Read her essay Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors.

WATCH

WATCH

In this video from WNDB2, author Rita Garcia Williams talks about why diverse books are important.

Lack of diversity in the Publishing Industry

A related issue is the lack of diversity in publishing. A 2015 Diversity in Publishing study3, created by Lee & Low Books with co-authors Sarah Park Dahlen and Nicole Catlin, looked at the demographics of the publishing industry itself, finding that 92 percent of respondents identified as not disabled, 88 percent identified as heterosexual, and 79 percent identified as Caucasian. In 2019 Lee & Low repeated the study4, co-authored by Laura M. Jiménez and Betsy Beckert, and found few changes. In fact, “the field is just as White today as it was four years ago.” Many people in publishing care deeply about the lack of diversity in publishing and want to fix the problem; however, the industry as a whole continues to struggle to change. For the sake of brevity, the minicourse will not explore this topic in depth, but you are welcome to review the below optional resources as time allows.

- Where is The Diversity in Publishing? The 2023 Diversity Baseline Survey Results5 – This article from Lee & Low shares the results of a follow-up survey on the demographics within the publishing industry.

- Comping White6 – This article published in the Los Angeles Review of Books examines how whiteness is perpetuated in the publishing industry.

BOOK REVIEWS

Just like the publishing houses are predominantly white, female, and heterosexual, so are the individuals who write reviews for the major reviewing sources. A 2015 survey conducted by SLJ7, for example, found that SLJ reviewers were largely white (88%) and female (95%). The resources below explain why the lack of diversity within the reviewing community is a concern, and a potential impediment to creating more diverse, authentic, and equitable library collections.

- When Whiteness Dominates Reviews – blog post by KT Horning

- BookExpo 2017: On Race, Reviewing, and Responsibility – by John A. Sellers

MISREPRESENTATION AND THE PERPETUATION OF STEREOTYPES

While the number of diverse titles is increasing, it is important to remember that not all diverse titles are “created equal.” Misrepresentation and the perpetuation of stereotypes of BIPOC continues, and as many scholars and practitioners argue may be as harmful as, if not more harmful than, no representation. To find out why, explore the following resources.

- Knowing Better, Doing Better – In this blog post, Elsa Gall explores how racist imagery and messaging show up in children’s literature and how they negatively impact the lives of children of color and Native youth.

- Awards Discussion Fodder: Thoughts on Stereotypes – In this blog post, Allie Jane Bruce unpacks the word stereotypes for us and discusses what this means for book evaluation.

- Critical Indigenous Literacies: Selecting and Using Children’s Books about Indigenous Peoples [posted on the NCTE blog8] – In this article, Dr. Debbie Reese focuses on unlearning stereotypical representations of Indigenous peoples and replacing harmful narratives with accurate information and understandings.

- Day of the Dead, Ghosts, and the Work We Do as Writers and Artists – In this blog post, author Yuyi Morales discusses the Day of the Dead and its misrepresentation in recent children’s books.

- ·Skippyjon Jones: Transforming a Racist Stereotype into an Industry – In this blog post, Beverly Slapin discusses the racist stereotypes present in the Skippyjon Jones books.

- Ghosts – This blog post from De Colores: The Raza Experience in Children’ Books9, discusses the cultural appropriation found in Ghosts by Raina Telgemeier.

ACT

ACT

Consider the following strategies for addressing issues of representation in your collection. Which strategies could you implement at your library?

- Evaluate your collection for titles that misrepresent and/or perpetuate stereotypes. If you decide to discard a title, be prepared to explain to teachers, parents, administrators, and the community why you made this decision. If you choose to keep titles that contain problematic representation, develop a plan to ensure that your users become critical readers/viewers who are able to recognize the misrepresentation and/or stereotypes.

- Provide professional development for teachers and parents about how to evaluate titles for cultural accuracy and representation. Use these resources to guide the discussion: Ten Quick Ways to Analyze Children’s Books for Racism and Sexism [PDF] by the Council on Interracial Books for Children; How to Tell The Difference: A Guide for Evaluating Children’s Books for Honest Portrayals of Raza Peoples from De Colores; How to Tell the Difference: A Guide for Evaluating Children’s Books for Anti-Indian Bias by Doris Seale, Beverly Slapin, and Rosemary Gonzales; Beyond Good Intentions: Selecting Multicultural Literature by Joy Shioshita.

- Provide alternative titles for teachers, students, and caregivers to use that accurately portray communities of color and Native communities – books that counter misrepresentation and stereotypes. For example, if a student wants to read the Little House on the Prairie series, suggest The Birchbark House series by Louise Erdrich.

- Engage youth in discussions about the impact of misrepresentation and stereotypes in literature. For ideas for how to do this check out these two blog posts by Jessica Lifshitz, a 5th-grade teacher in Northbrook, IL. – Teaching Our Students That What We Read Affects The Biases and Stereotypes We Hold and Helping Students Confront and Examine Their Own Biases Using the Images on Covers of Picture Books.

IMAGES OF PRACTICE

IMAGES OF PRACTICE

Elementary school librarian Haley Ferreira stepped into her first full-time school library job in the middle of the school year and immediately noticed gaps in the collection. Her school serves a student population that is 58% Black and 37% Latinx, and she knew that she needed to work toward a collection that reflected and celebrated their diversity. Watch the video below, in which Ferreira discusses some of the steps she took in her first six months to assess and improve her collection.

FINDING TITLES

Two of the biggest reasons giving for not including more diverse books in the library or the curriculum is, “I can’t find them” or “They aren’t available from my library’s vendor.” While both of these statements might be true, they can no longer be used as excuses for not collecting diverse titles. WNDB provides an extensive list of resources you can use to find diverse titles. There are also a number of book awards that celebrate diverse titles. And, there are a growing number of publishers that devoted to publishing diverse books including:

- Al Salwa (Arabic children’s books)

- Arte Publico Press (literature by Hispanic writers)

- Children’s Book Press, an imprint of Lee & Low (bilingual English/Spanish picture books)

- Cinco Puntos Press (adult and children’s literature, and multicultural and bilingual books from Texas, the Mexican-American border, and Mexico)

- East West Discovery Press (multicultural and bilingual books in 50 + languages)

- Groundwood Books (Canadian publisher of books for young readers with a focus on diverse voices)

- Just Us Books (Black interest and multicultural books for children and young adults)

- Lee & Low Books (diverse books for young readers featuring a range of cultures)

- Oyate – (books and other resources that lift up of writing and illustration by Native people from across North America)

- Piñata Books, an imprint of Arte Público (juvenile and young adult books focused on Hispanic culture and by U.S. Hispanic authors)

- Roadrunner Press (fiction and nonfiction for young readers focusing on the American West and America’s Native Nations)

- Tu Books, an imprint of Lee & Low (diverse middle grade and young adult speculative fiction)

- Shen’s Books, an imprint of Lee & Low Books (Asian/Asian American books for young readers)

It is incumbent on us as professionals to educate the administration (principal, bookkeeper, system-level purchasing department, etc) on why it is critical to make sure purchasing regulations include not only large vendors, but also small presses, independent bookstores, alternative presses, etc. Policies can always be changed; it may take time, data, and continued advocacy on our part.

ACT

ACT

Now that you’ve completed this module, try evaluating the following from a racial equity lens:

- the reviews you are reading;

- the selection tools you and your library rely on;

- the vendors your library or/and the system utilize;

- the collection development practices that are included in your library’s policies; and

- who is selecting/buying books & other resources for your library and how intentional they are in the decisions they make to acquire diverse and reflective texts written by and about communities that are often marginalized.

CONNECT

CONNECT

Join the conversations taking place on social media about diversity in children’s literature. Here are a few blogs to help get you started:

- Home Page

- Section 1: Foundations

- Module 1: Introduction

- Module 2: History of Race and Racism

- Module 3: Defining Race & Racism

- Module 4: Implicit Bias & Microaggressions

- Module 5: Systems of Inequality

- Module 6: Indigeneity and Colonialism

- Module 7: Exploring Culture

- Module 8: Cultural Competence & Cultural Humility

- Module 9: Racial and Ethnic Identity Development

- Module 10: Unpacking Whiteness

- Module 11: Confronting Colorblindness and Neutrality

- Module 12: Equity Versus Equality, Diversity versus Inclusion

- Module 13: Allies & Antiracism

- Section 2: Transforming Practice

- Module 14: (In)Equity in the Educational System

- Module 15: (In)Equity in Libraries

- Module 16a: Building Relationships with Individuals

- Module 16b: Building Relationships with the Community

- Module 17: Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy

- Module 18: “Leveling Up” Your Instruction with the Banks Framework

- Module 19: Youth Voice & Agency

- Module 20: Talking about Race

- Module 21: Assessing Your Current Practice

- Module 22: Transforming Library Instruction

- Module 23: Transforming Library Space and Policies

- Module 24a: Transforming Library Collections Part 1

- Module 24b: Transforming Library Collections Part 2

- Module 25: Lifelong Learning for Equity

REFERENCES

- https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/literature-resources/ccbc-diversity-statistics/ ↩︎

- https://diversebooks.org/ ↩︎

- https://blog.leeandlow.com/2016/01/26/where-is-the-diversity-in-publishing-the-2015-diversity-baseline-survey-results/ ↩︎

- https://blog.leeandlow.com/2020/01/28/2019diversitybaselinesurvey/ ↩︎

- https://blog.leeandlow.com/2024/02/28/2023diversitybaselinesurvey/ ↩︎

- https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/comping-white/#! ↩︎

- https://www.slj.com/story/survey-reveals-demographic-of-slj-reviewers ↩︎

- http://www2.ncte.org/blog/ ↩︎

- http://decoloresreviews.blogspot.com/ ↩︎

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3).

Bishop, R.S. (1982). Shadow and substance: Afro-American experience in contemporary children’s fiction. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Larrick, N. (1965, September 11). The all-white world of children’s books. Saturday Review, pp. 63–65, 84–85.